“There is first of all the repair of the human body. The body has an awesome capacity to repair itself in ways that are to the ordinary observer visible (e.g., the healing of a cut) and invisible (e.g., the continual self-repair of DNA, or the recently discovered capacity of the human heart to repair itself). But it can’t do that, and will cease doing it, without being fed and watered.” (pg.33)

What I found interesting about this passage was that it was conveniently allocated in a chapter regarding the differences between gender in the way that we repair. Spelman added a reference which touches on our basic biological fundamentals as humans – the fact that every single human being is constantly repairing themselves without the awareness of it. No matter the demographics, man, woman, white, black, young, old, educated, or not, etc., our bodies are already hardwired to repair what has been damaged. This illuminates the basic similarities of every human in a passage which was intended on highlighting the distinctions between them.

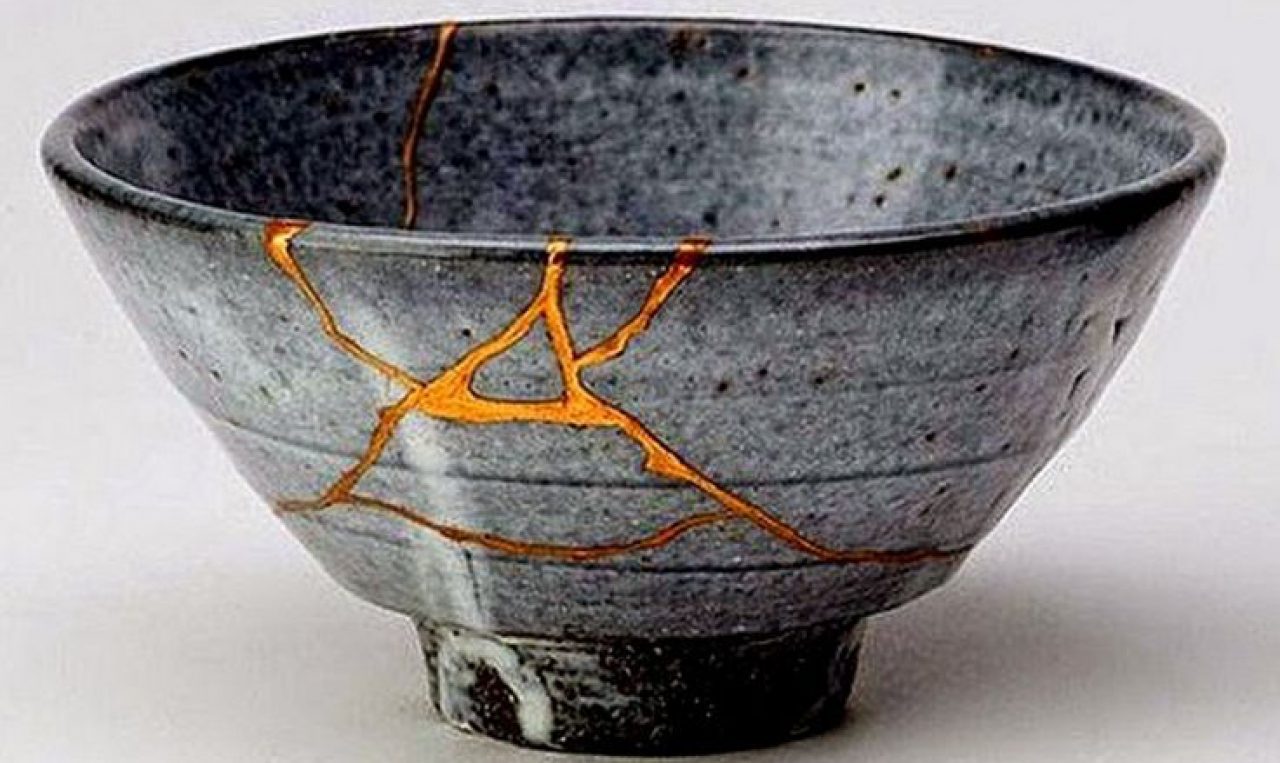

Maybe this biological occurrence is where our need to fix everything stems from. The outside world where things break and do not mend is unsettling to us. We have an unconscious need to fix everything that once was, because our bodies do not break and then stay broken. When we fall and scrape our knees, we do not bleed out until there is nothing left. We scab and mend, and continue moving forward as things had been once before. It may leave a scar, but we are shown that when damage happens we still repair. But when a dish shatters, unless we place it back together, it will remain broken. Which again, doesn’t sit right with what we have been taught from the beginning of time from the way our bodies work. When we fix things, whether it be an object or a relationship, we expect to return to the way things previously were despite the damage. After repairing a relationship, things never really go back to the normalcy possessed before damage. The relationship is either weaker or stronger, likewise with the repair of objects. Sometimes the repair allows the object to function better or be better equipped to protect itself against future damage, and other times the repair allows the object to continue being, but with more fragility and vulnerability than before.

This piece of the chapter brought the theories of Spelman’s book to a whole new understanding for me. The fact that our bodies, before being adulterated by salves or medicine, has the basic function to repair and heal, goes even further into the foundation of Spelman’s claim in this book; that humans are prone to repair. This part of the text allowed myself, as the reader, to not only understand the repair theories but to expand on them from my individualized sense of the world, and I expect it will do the same for others who make sense of the world in similar ways to myself. So, now to expand on this idea, I ask, can this biological need and desire to repair then be somewhat of an impediment for humans in interactions with the outside world?

“The story of H. reparans throws into sharp relief how we humans have responded to the fact of being creatures who are inherently limited by the resources at our disposal, who are subject to the ever present possibility of failure and decay, who sometimes seek continuity with the past, and who face the necessity of deciding whether or not to patch up relationships with our neighbors – in short, it reminds us of some facts about the human condition that perhaps we tend to find disturbing. And yet, once introduced, Homo sapiens as repairing animal typically invites grasps of recognition and suggestions that we’ve barely begun to explore the many projects and habitats of H. reparans” (pg.139)

People tend to feel restrained or stuck when things don’t go their way or don’t come easy. Our immediate reaction to not getting what we want, whether it be a physical thing or a result/reaction, is to stop trying. Of course over time we realized that this is a silly response and we must make do with what we are given but this response sometimes restrains us from reaching our full potential. This is the difference between humans and all other living things; we are the only organism that ever restricts itself from growth.

As said before, we see that with our bodies when we are damaged we heal and therefore it feels unsettling when things don’t repair on their own, like the example of a dish shattering – staying broken until we take action to glue it back together. With the outside world, where our emotions operate, we see that healing isn’t a natural occurrence and in that we create mental blocks. When I used to do competitive cheerleading at an international level (obviously, some serious stuff), we were always pushed to learn new skills, and until the skill was mastered we knew there was an almost ensured possibility of falling. But to us that meant progress, so we got back up and tried again because we knew were one fall closer to achieving the skill; or one failure closer to success. One season, right before competing at the world championship, I thought myself into a mental block with tumbling, (the running and doing flips and stuff), due to all the external pressures of trying to please coaches and teammates. I terrified myself with thoughts of failing to a point where I wasn’t even able perform skills I had mastered for years. I would go for the skill, get to the transition for it, (if you want to get technical) a round-off then the back-handspring and rebound up for the skill and just freeze, I was stuck. I knew not being able to even try the skill was seen as worse than just falling, but my brain was too messed up with anxiety to even communicate to my body what to do. The fact that I stopped myself from doing something I was completely physically capable of, due to fear of failure, is extremely stupid when really thinking about it. To have fear of failure take over the body, and stop one from progressing to maximum potential as a person is disturbing. In a more universal context, to have the fear of giving the wrong answer in class stop someone from raising their hand to try answering, is disturbing; The idea that we actually restrict ourselves from reaching our full growth and potential is disturbing.

To go deeper into the fear of failure and where it stems from, again relates back to our biological needs to repair. As our always bodies self-repair, that unsettling feeling of something being broken also emerges when something just isn’t perfect. In our society and through human interactions we, at some point, began to see ‘imperfect’ as needing to be fixed and failures as the inability to fix. And this idea translated into the way we look at ourselves and other people. We all have thoughts similar to: “If I was prettier or more handsome, maybe people would like me more ” or “If I was smarter or funnier, I would be better off”. We even have some thoughts as ridiculous towards others as “She would be more attractive if she did something with those ratty curls in her hair” or “He would be much better looking if he would put some meat on those bones”. We see imperfection or flaws of ourselves and others, or just of humans in general, as needing to be fixed. And by seeing them as needing to be fixed, we think there is something wrong with them. Which is again, disturbing. That we decide that people have something wrong with them if they are not up to societal standards or even our own standards, or that we even have standards for how we think people should be. 1950’s mental institutions or asylums is a classic example of this occurrence. A person is seen with a flaw or problem and we think they need to be fixed. And if we can’t see a fix to a person’s ‘damage’, like an object it is declared not worthy of fixing and disposed. Until fairly recently in our history, people would actually give up their own children if they had physical or mental disabilities. Meaning we, at one point, deemed people unworthy of love or care or even a second glance, if they were perceived as “imperfect”. That is unbelievably disturbing.

Our need to repair is an inexplicably complex notion. Our bodies are constantly repairing; we all do it. We break and mend; We wound and heal. It is an amazing and fascinating gift received by all living creatures. Our body’s internal repair shows no discrimination, yet somehow when this phenomenon is brought into the outside world via the human mind, (an internal organ which is treated with the body’s indiscriminate means of repair), in terms of social interaction, it turns into just that; discrimination. We have mixed up our need to ‘repair’ with a need to ‘fix’. Our bodies repair, go back to a state previous to damage. Imperfections cannot be repaired, because they were never perfect; they can only be fixed. We see failures as imperfections, that are wrong, and as damage that needs to be fixed. We tell ourselves that being imperfect makes us incompetent of success, and we tell others that too. I am not only talking about complexion or character of a person being deemed imperfect and wrong but also mental and physical disability, race, and sexual orientation being part of the discrimination. In fear of this discrimination, we have fear of being imperfect, and needing to be fixed, or of failure, and being deemed unfixable, and essentially scare ourselves into restricting our own growth and potential. “Homo sapiens as repairing animal[s]” cannot progress with that unsettling or ‘disturbed’ feeling of something being damaged, or broken, or wrong, or imperfect. And the “recognition” or “suggestions” of this explore “… some of the facts about the human condition that perhaps we tend to find disturbing”.